Our daily routine was familiar, comfortable by now.

The doctor of the day assigned all of the new consults, dividing them up among the team. We all split up and headed out to see our new patients and check in on patients we were following from before. We would reconvene later in the morning to present the new ones to our attending and then round on them as a group.

The doctor of the day assigned all of the new consults, dividing them up among the team. We all split up and headed out to see our new patients and check in on patients we were following from before. We would reconvene later in the morning to present the new ones to our attending and then round on them as a group.

The patient assigned to me was an 18-year-old girl who had just given birth to her second child. The OB team was concerned about possible depression. I opened her chart before going to see her, scanning for the basics about her case. She had received no prenatal care during this pregnancy. She had given birth in the bathtub at a friend’s house. EMS arrived shortly, just after the afterbirth had washed down the drain, and mother and baby were brought to Grady for postpartum care.

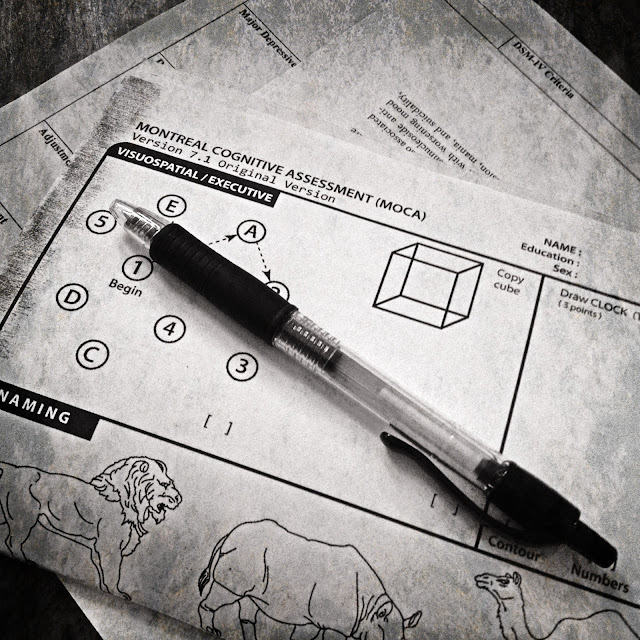

I gathered the few things I carried with me to see patients: a few sheets of paper, folded in half; my favorite pen with the ultrafine tip.

She was awake and sitting up when I reached her room. Her hair was tied back neatly, her face appeared freshly washed. She was sweet, spoke softly, cooperatively answering all of my questions.

She hadn’t seen the baby much since she’d arrived at the hospital the day before and that was how she wanted it: she did not want to bond with him. She was totally overwhelmed by the thought of having another baby to take care of, in addition to the 18-month-old daughter she already had at home. She wanted to give this new baby up for adoption.

It was a slow day on consults and she was my only new patient, so I had plenty of time to spend with her. I mentally ran through my checklist, making sure that I took a thorough history and that I had every piece of my metal status exam and any other pertinent information I would need to make a good presentation to my attending later that hour. Her HPI – or History of Present Illness – was confluent with her Social History, as they almost always are in patients with psychiatric symptoms. In her case it was interesting, and talking with patients is almost always my favorite part of taking care of them. I think that if there is one thing that I have any natural talent for in medicine, it is just the ability to talk to people. And I think I am okay at it because I just genuinely enjoy it.

I asked everything I could think of about her situation. We talked about her ex-boyfriend and the father of this baby, we talked about how their relationship had been and why she had ended it. We talked about her family and her relationship with her parents and her grandmother, who lives with the family. We talked about her plans for the future, about how she is about to graduate from high school and how she wants to go on to college and what she wants to study. We talked about why she doesn’t feel up for raising the son she just gave birth to, and about how her family is pressuring her to keep him. We talked about how she wants to be a good mother to the baby she already has, how she wants to provide a better future for her daughter.

Appears well-groomed and appropriately dressed. Good eye contact. Speech spontaneous, appropriate, normal rhythm and tone. Endorses some depressed mood, but does not meet criteria for Major Depressive Episode. Denies suicidal and homicidal ideation. No psychotic symptoms, no evidence for any history of mania or anxiety. Mood stable. Affect euthymic, full range, mood-congruent. Thought process logical, future-oriented, goal-directed. Cognitively intact. No past psychiatric history. No known family psychiatric history. No other medical issues. No medications, no allergies.

This was the first rotation that I have been officially “presenting” patients to attendings. In medical training, this is basically an exercise in synthesizing pertinent information about a patient based on their clinical presentation and their medical record and then giving a succinct, cohesive oral presentation to the attending physician about what is going on. Depending on the service and the attending, these presentations can be more informal or very formal, and there is sort of a basic formula that you are supposed to go through for every patient, including all pertinent information in the correct place in your presentation, starting with the patient’s “chief complaint” or presenting symptoms.

Essentially, what you are trying to do is to describe how and why this patient came to be where they are now, both literally and figuratively – to create a story about what is going on with them that will paint a clear picture in the listener’s mind, building a case to support the diagnosis you have come up with and justifying your proposed treatment plan for their care. It is tricky, though,when you are learning how to do it. It’s hard to do well, much harder than it sounds, harder than I had thought it would be before I had to do it myself. And it gets even trickier when the patient has multiple issues going on, or if they have a long or complicated history, or a host of different medications. Incomplete records and poor self-reported history compounds the difficulty level, and on top of that, every attending has his or her own way of doing and thinking about things, and all they tend to want presentations done a specific way – some want certain information in certain parts of the presentation and some want that information left till a different part of the story, or left out altogether. It’s almost like a game, and it doesn’t take being corrected very many times to figure out what special thing your instructor du jour wants done in their patient presentations, but there is always a bit of a learning curve.

This was one of my last weeks on psychiatry. I was finally starting to feel like I was getting the hang of presenting and writing notes and getting all the necessary information from my patient interviews.

It had been a pleasant conversation with this patient. Hard, sure. She was definitely in a tough spot, facing a pretty heart-wrenching decision. But it wasn’t some horrible, senseless, hopeless tragedy, like many other patients’ situations that I have seen. This was a fairly straightforward case, nothing spectacular or even really notable from a psychiatric perspective. I really enjoy teenagers and she was easy to talk to. I cared about her, listened to her for a long time – I liked her. But it wasn’t until I stood up to go, telling her that I would be back later with my team and that we would be around to talk with her if she ever wanted us to, when she did something that surprised me. She thanked me, genuinely and emphatically. And not just with a simple “thank you”. She went on: “it was so nice of you to come and talk with me. I really appreciate it. It’s nice just to be able to talk about this stuff. It really helps.” She smiled at me. I was stopped short.

From my end, from the psychiatry consult service perspective, it was pretty simple. No depression, no anxiety disorder, not even really any adjustment disorder. Just a teenager with a hard decision to make, doing really pretty well, all things considered. Certainly nothing she needed to be “treated” for. I had screened for all the major things we worry about, made sure I had all the pertinent positives and negatives I needed for my note and my presentation.

But it really hadn’t even occurred to me until she thanked me that maybe I had done something for her. That maybe just my presence, my being there, my having sat down with her and listened to her, asking questions occasionally, nodding, smiling, knitting my brow, saying “tell me more about that” and “that must be really tough”…. had been at all therapeutic. And even worse, it hadn’t occurred to me that she had needed it.

I felt awful. There was no Axis I pathology here, no personality disorder, no capitalized-letters DSM-IV-diagnosable psychiatric condition… but there was a person. A person going through a rough time. A person who was hurting. And overwhelmed. And probably feeling like she didn’t have enough support, or anyone she could talk to that didn’t have some sort of vested interest in the outcome of her decision for reasons of their own. And THAT doesn’t take any sort of special training to recognize. A person having a hard day, or week, or year? Someone who just needs to talk? We’ve all been there. It is all the more unbelievable and awful to me that I missed it because I am in that position, frequently and currently. How many times just in the past two weeks have I felt unspeakable comfort and enormous relief after a good talk with someone who cares about me?

How quickly I had forgotten the difference between what I was "supposed" to do and what I was supposed to do in that visit to my patient. There were educational objectives to be met; my grade for the rotation is based in part on my presentations and my notes, my assessments of patients and my recommendations for treatment based on those assessments. But my reason for being here - anyone in healthcare's reason for doing this work - is to care for people when they need it. And those two things, the educational aspect and the patient care aspect, are not always one and the same.

How easy to get mentally stuck in learning mode, and how easy to forget that, simultaneously, I also need to be in caring mode. It is totally possible, just requires a little bit of conscious reminding myself sometimes. I wish it didn’t. I would always rank caring over learning in importance if asked, but maybe it takes a little more thought than that in actual practice. I think that sometimes, as a medical student, it can feel like you have very little real impact on patients or their care, and then it's harder not to just worry about whether or not you are checking off all the appropriate boxes needed for your evaluations. Or maybe it's just me. Either way, my visit with this patient exposed this tendency of mine. It genuinely surprised me, and it felt disheartening to realize that as much as I may think that I truly care about people and that I always want to put my patients first, I fall short way too often in that regard. I thought about this 18-year old girl and felt my acute disappointment at not having recognized what she needed for a long time after that visit. I hope that her story will help remind to me stay vigilant in remembering what my true assignments here are.

No comments:

Post a Comment